Q: Is there a story in your collection, Breathing is How Some People Stay Alive (Guernica Editions, 2026), you wish you could revise or change in some way?

A: Yes. There is a story in the collection that doesn’t work, or it’s not doing what it really needed to do when I dreamed it to life years ago. I don’t know if every reader could pick it out before reading this, but I think some might.

This story came to life after I had spent two weeks in NH losing things – from car keys to my phone, to my bathing suit, my running shoes – and on that trip I lost an expensive pair of sunglasses. We’ve never had a lot of money, but at that time, we were in such deep debt that I knew I’d never be able to replace them. They weren’t even mine, my brother took them from the lost and found at work – after they went unclaimed for six months.

The person who loses things all the time is haunted by the one thing, the one person, he lost, and cannot get back – his sister, who was abducted as a child while in his care. These lost things, or losing track of things, carries through to adulthood where he now writes children’s books. He’s created a popularfictional world where his sister lives, so that he doesn’t have to admit she’s gone, that he lost her.

This loss, the grief, is a fracture that never heals. He limps around unable to connect thoughts and as his dead sister’s 30thbirthday approaches and a detective from the past shows up with evidence that she is, in fact, dead, the main character trips over every thought and cannot function.

I revised this story dozens of times. It has been rejected by a handful of literary magazines. And it was in the final edits with the publisher that my own thoughts fractured and I realized why I couldn’t get inside of it and feel that any part of the story belonged to me. I wanted to remove it entirely, but as a connected collection, two of the characters exist elsewhere and what happens in this story feeds the narrative of later stories.

I wrote the first draft the year my dad died.

Diagnosed with a rare blood disorder, I had dismissed his mortality as easily as one might drop a set of car keys on a table. He once begged me to let him stay over in Toronto an extra night, and I rejected him, told him it would be too complicated. My parents didn’t have a pleasant divorce, and it was my daughter’s birthday that weekend. He was in hospital a week later, dead three months after that.

In all the revisions, I never once made the connection. My father wasn’t a lost child, a set of car keys. Convinced I was trying to write some kind of murder mystery with a provocative hook, I didn’t feel the pain until it was too late. I’d thrown a stone into a swimming pool and now I had to stand on the edge staring at the bottom without any way to retrieve it. I’d written into the story places of my childhood that are most emotionally connected to my dad, to my trauma. The Welland Canal. Orchard Park. St. Alfred’s Church. The QEW. I still can’t drive over the Burlington Skyway without thinking about him, and here I’d written a story about a man who sleep-drives from Toronto to St. Catharines to fish around a dirty creek for evidence his sister is still alive.

Once There Was A World is in the middle of the book, and when you read it, I want you to know that I lost something and there are days, weeks, sometimes months when I dream about how I might get it all back.

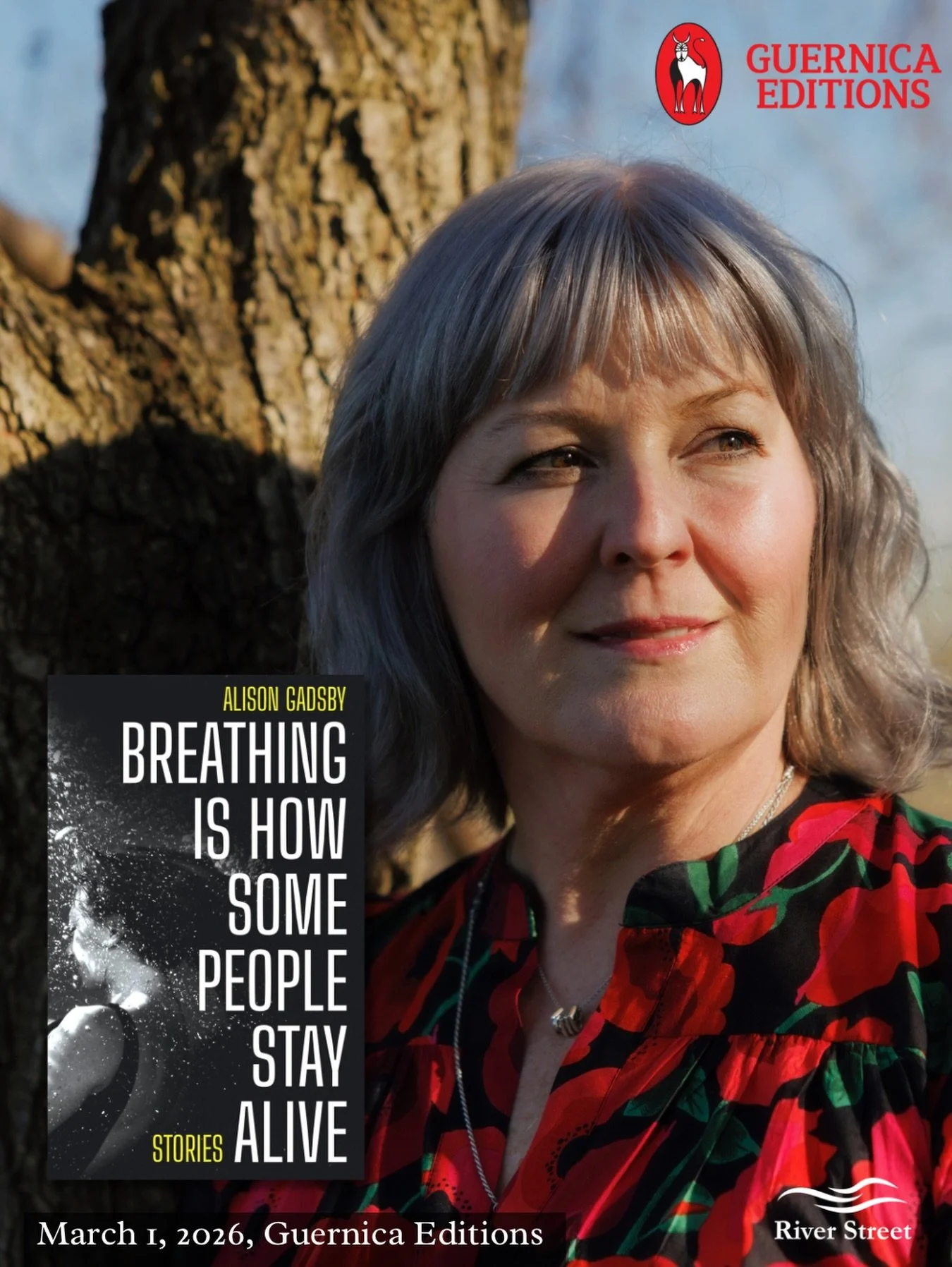

Breathing Is How Some People Stay Alive blurs the lines between horror, catastrophic speculative fiction, and psychological realism in a collection that might best be described as weird fiction. These connected stories offer dark reconstructions of lives brimming with desperate loneliness. They allow us to bear witness to the life-altering love of sisters, brothers, mothers… the life-altering love that buoys them as they struggle to stay afloat in the wake of childhoods they merely survived.

Alison Gadsby writes in Tkaronto/Toronto where she lives in a multigenerational home that includes several dogs. Her writing has appeared in various literary journals, including Blank Spaces, The Temz Review, The Ex-Puritan, Blue Lake Review and more. She is the founder/host of Junction Reads, a prose reading series.