This story begins in 2022, Padua, midwinter. Across the city a debate is raging. It concerns a woman whose name I only recently learned: Elena Lucrezia Cornaro Piscopia, the first woman in the world to earn a Ph.D. City councillors Margherita Colonnello and Simone Pillitteri have proposed to place a statue of Piscopia in the town square — a notable historical woman to join the effigies of notable historical men. This suggestion has sparked outrage across the country.

It hadn’t occurred to me to type “first woman Ph.D.” into Google. I kicked myself for my lack of curiosity. After all, I was going to be the first woman in my family to earn a doctorate. It had been the hardest thing I’d attempted in my life so far, partly because I still felt, deep down, that I wasn’t entitled to the pursuit of an intellectual or creative life. I felt I was getting away with something, fooling the academy, and it was only a matter of time until I was exposed. As I’ve come to understand, this isn’t an uncommon experience, particularly for first-generation scholars, or scholars who have disabilities, or who identify as queer, BIPOC, or women.

I wondered if Piscopia had felt this way, too. As a woman in the 1600s, she’d had to fight for her education. Piscopia was born to unmarried parents, a peasant woman and a nobleman. Her father tried to arrange betrothals for his daughter, but she rebuffed each suitor’s advances, preferring the company of her harpsichord and philosophy books. Women weren’t allowed to enter university at the time, but her father was able to pull a few strings for his prodigious daughter. Even then, the residing Cardinal Gregorio Barbarigo opposed Piscopia’s request to graduate with a doctorate in theology, arguing that it was a “mistake” for a woman to become a “doctor.” He eventually let her graduate with a degree in philosophy instead.

I looked up the year 1678. Le Griffon, the first European ship to sail on the Great Lakes of North America, prepares for her maiden voyage. The first fire engine company in what will become the United States goes into service in Boston. The Pilgrim’s Progress, a text that 334 years later I’d be forced to read in an undergraduate literature class, is published in London, England. Rebel Chinese general Wu Sangui takes the imperial crown and dies of dysentery months later; Franco-Dutch battles are instigated, ceasefires called, and in Padua, at the age of thirty-two, Piscopia receives her Ph.D.

•••

At almost 90,000 square metres, Prato della Valle, or “Meadow of the Valley,” is the second-largest square in Europe. At its centre is a green island surrounded by a small canal and bordered by two rings of statues, all of historical men. I recognize some of the names: Galileo, father of observable astronomy; the artist Mantegna, famous for his use of perspective and anatomical detail; and the eighteenth-century sculptor Canova, renowned for turning stone into flesh.

Two of the pedestals in Padua’s elliptical square are empty. It seemed fitting, the city councillors proposed, that Piscopia might rest on one of the empty pedestals, that hers might become the first monument honouring a woman in the city’s historic centre. As art historian Federica Arcoraci points out, spending time among the square’s all-male statues has “an impact on our lives and collective imagination,” and the “Prato della Valle regulation of 1776 never ... prohibited the representation of women.”

Across the country, critics protested Piscopia’s inclusion in the square. Some claimed that a statue of the first woman Ph.D. would be out of context with the square’s history. Others believed that to include a female statue within the pantheon of male statues would be an act of “cancel culture.”

Colonnello and Pillitteri walked back their original proposal, but they still insisted that a statue of a woman be allowed in the square. It didn’t have to be Piscopia — they were willing to erect her monument elsewhere. But the city had to decide on another historical woman instead — for instance, the nineteenth-century painter Elisabetta Benato-Beltrami or the writer Gualberta Alaide Beccari.

“The important thing,” said Colonnello, “is that we have raised the debate about the underrepresentation of women among monuments and it is now very clear to all politicians that we need a very good statue of a woman in a very good place.” She pressed on: “We now need to decide where and who. But I think we will eventually settle on the square — it is very huge and there is lots of space.”

I looked up an image of Prato della Valle. Colonnello is right. At the size of almost two football fields, it’s massive.

Why was there such opposition to the inclusion of a woman in such an enormous space? It appeared that the controversy wasn’t about the square itself but what the square symbolized. It represented the boys’ club, cultural memory, the legacy of genius. The square represented representation itself.

What the Piscopia debate exposed wasn’t just the scarcity of statues celebrating notable women — of the thousands of statues in Italy, fewer than two hundred depict women — but the historical resistance to simply recognizing women’s achievements. This resistance isn’t unique to Italy.

After reading about Elena Piscopia, I went walking through the squares, parks, and boulevards of Montreal, my own city. This was where I’d lived for much of my life — a place I kept returning to for its promise of art, freedom, and community. Yet, like the Prato della Valle, it was still filled with statues of European men.

Where were the women? I found myself asking this as I stood below the Sir George-Étienne Cartier monument at the foot of Mont Royal. Not the angels and goddesses but the monuments to historical women. Where could I find them?

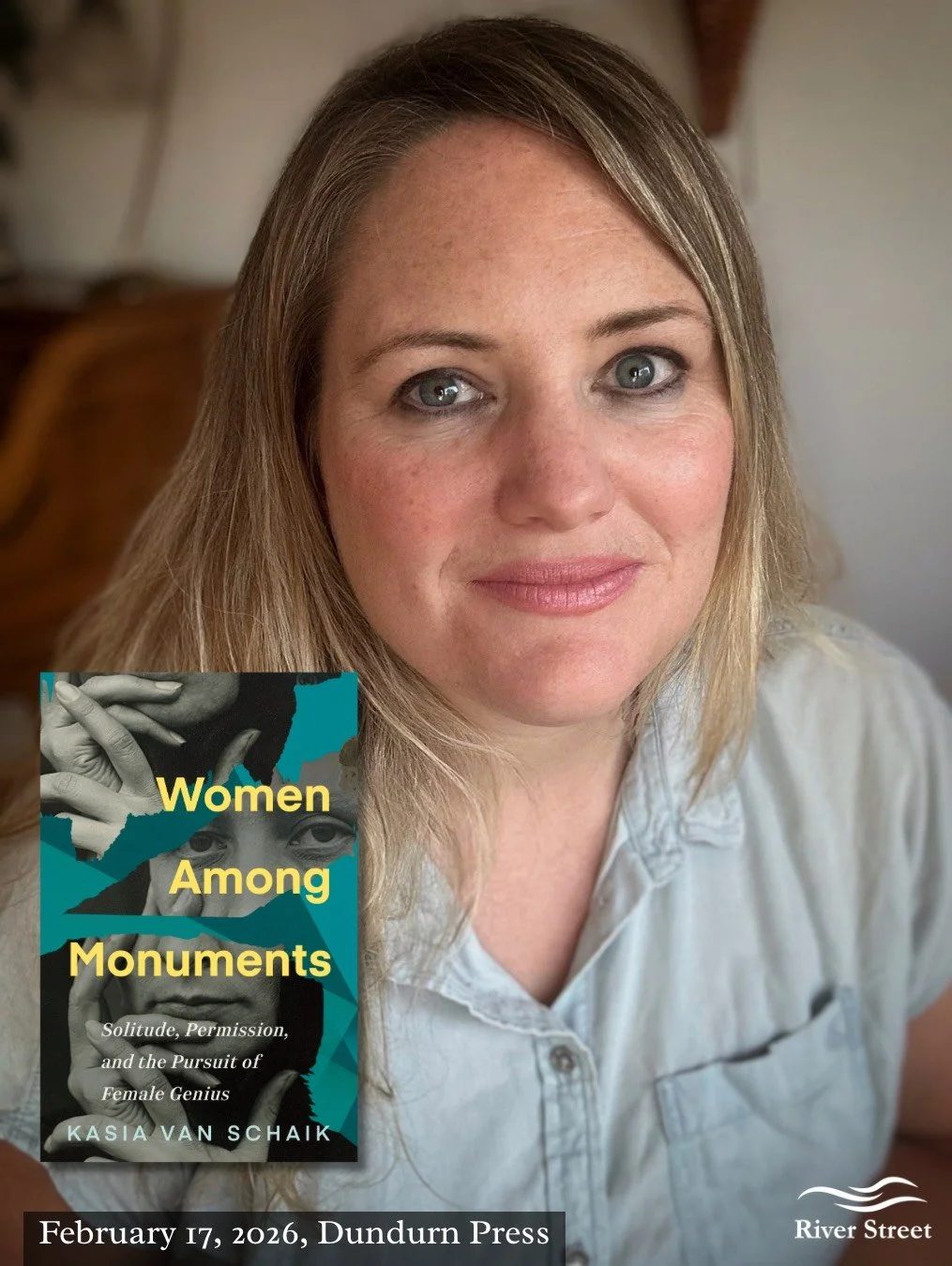

Excerpt from Women Among Monuments by Kasia Van Schiak. Published by Dundurn Press. Copyright Kasia Van Schiak, 2026. Reprinted with permission.

Women Among Monuments by Kasia Van Schiak

About Women Among Monuments:

A lyrical meditation on the enduring obstacles women artists and writers face in a world still unaccustomed to recognizing female genius.

What does it take for a woman to don the mantle of genius — a title long reserved for male artists? From her studies in Montreal to a dead-end job in Berlin, a midnight tour of Paris, a bankrupt art residency on the Toronto Islands, and a mysterious sculpture garden in the Karoo desert, South African—Canadian author and professor Kasia Van Schaik considers what it means for a young woman to call herself an artist and claim a creative life.

Drawing on a diverse web of literary and cultural sources and artistic icons — from Georgia O’Keeffe to Ana Mendieta, Gertrude Stein to Jamaica Kincaid, Leslie Marmon Silko to Bernadette Mayer — Women Among Monuments asks, What, beyond a room of one’s own, are the necessary conditions for female genius? Where does the inner flint of artistic permission come from? What is the oxygen that keeps it burning?

In her memoir interwoven with incisive biographies of female solitude, constraint, and perseverance, Van Schaik blazes a trail for more inclusive artmaking practices, communities, and monuments.

Kasia Van Schaik is the author of the linked story collection We Have Never Lived On Earth, which was longlisted for the Scotiabank Giller Prize. Her writing has appeared in Electric Literature, the LA Review of Books, the Best Canadian Poetry, and the CBC. Kasia holds a PhD in English Literature from McGill University and lives in Montreal.